Today I have been mainly photographing an International Space Station's Solar Transit. This is when the ISS passes across the face of the sun creating a silhouette of its shape. Whether you can view a solar transit like this depends on where you are on earth at the time of its passing. Luckily, today it was viewable from some parts of the UK.

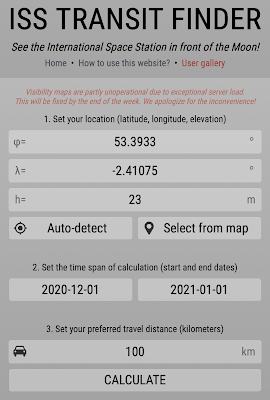

To view a transit you need to plan in terms of location and time, prepare your equipment and execute your plan at exactly the right time. Finding out where it will be viewable is quite easy nowadays using online resources. I use ISS Transit Finder to look out for and plan solar and lunar transits by the ISS. Here is an outline of the procedure:

Planning

- Go to transitfinder.com

- Enter your location by using 'Auto-detect' or by entering your latitude and longitude co-ordinates

- Enter the dates in which you are interested - you can only go up to 30 days in advance

- Enter how far you would be willing to travel in km (100 is good number to choose)

- Click the 'Calculate' button.

This will take you to a screen that shows you the next solar and lunar transits which can be viewed from or near your location, in date order.

From the above image it can be seen that when I was planning this, the next solar transit was 2020-12-05 (US date format) which is today. However, the quality of view was only going to be 2 star from where I live in Tyldesley with only 1.21 seconds of viewing time and the ISS is only just skirting the bottom of the sun. Clicking on the 'MORE INFORMATION' button revealed more detail:

Clicking on 'SHOW ON MAP' produces a map of the transit path showing my location as a red pin and an ideal location on the line of maximum viewing time with a green pin.

Anywhere along the central line would give a viewing of 2.37 seconds. So I closed the pop up box and zoomed into the map to find a good spot. It was at this point that my friend Paul Richardson suggested Dunham Massey, as it's an area not far from our homes and almost exactly on the central line. He suggested a free car park on Henshaw Lane, but when I actually got there it wasn't in the best position. However, I soon found another spot just 100 metres up the road and Paul joined me there.

Preparation

The preparation to get an image of the solar transit mainly requires a lot of thought. There are two main methods I considered:

- Fire a rapid burst at exactly the right time

- Take some video of the passing

Having two DSLR cameras, I decided to try both methods.

The first method depends on having the right camera settings and firing a burst exactly on time. Luckily, I've imaged the sun a few times now, the first time being capturing the

Transit of Mercury back in November 2019 - you can read about that

here. So I had an idea about the settings, although clouds can sometimes play havoc with what you think should be correct. I set the camera to fully manual mode, and used

ISO 100, an aperture of

f/9 and a shutter speed of

1/1000th of second and practised in my back garden.

The second method doesn't require exact timing as the video can be started early and left running. Although you will be sure of capturing it that way, the resulting images may not be as sharp for such a small, fast moving object. A high frame rate and fast shutter speed would be needed.

To help with timing, I downloaded an

accurate time app for my phone called '

Atomic Clock' which is synced to internet time and which gives the time in milliseconds. My

shutter release cable and two

home-made solar filters made for the

Mercury Transit were also needed. The shutter release cable helps avoid unwanted vibrations often caused by touching the camera.

The solar filters are essential for viewing the sun to avoid damaging your eyes and the camera sensor. You can read how I made mine

here. I never look at the sun though the eyepiece, only on the back screen of the camera. It also helps to use a towel or sheet placed over the camera and your head when viewing the camera screen, to cut out unwanted light from the sun.

I decided I'd set up two cameras on tripods each with a solar filter (one for video and one for stills) to ensure I got some record of the transit. I'd start the video recording early and leave it running, then concentrating only on the stills camera which I would fire a three second burst activated by the shutter release cable. My camera, a Nikon D500, has a large RAW file buffer and can shoot up to 200 continuous frames at 10 frames per second, although there is somethings a brief pause after 50 frames. I used a 500mm f/4 lens with a 2x teleconverter to give 1000mm (or 1500mm in 35mm terms).

Because the ISS was only going to be a tiny silhouette against the very bright sun, I decided that the shot I wanted was a composite of its path across the face of the sun. A single image like the one below isn't all that interesting. So all I'd need to do was hold the shutter down firing rapidly as it passed by - easier said than done and only one go at it!

Execution

Having done the preparation, the final part was to put the plan into action. I arrived early to cope with setting everything up correctly and doing a few test exposures. Paul turned up shortly afterwards and when we were both ready we just had to wait for the right time. Paul was shooting video though an 400mm scope with a 2xBarlow and a DSLR camera.

Anxiously checking the Atomic Clock app, I called out the time every now and then waiting for 13:16, at which point I held down my shutter release and fired away. I carried on doing it for three button presses which took about 200 shots each until 13:17 arrived, at which point I knew it the ISS had gone.

Before we knew it, it was all over. We quickly checked the backs of our cameras but neither of us could see anything except the sun. I thought I'd blown it. I'd have to wait until I got home to find out that I'd actually captured it! I sent a text to Paul to tell him I had and that he should have something too. He later confirmed that he had. Below is an animated GIF which I made from the individual frames.

Unfortunately, my video recording was very underwhelming as expected. Having used my best equipment on the stills, I had to use a full frame camera on a 300mm lens plus a 1.7x teleconverter for the video. Although I have captured something, it just wasn't long though to record the tiny ISS in any detail.

Processing

The final part of this little project was to produce a final image of the ISS transit shown below. This was done by importing the images into PhotoShop via a script which loads them into an image stack, with many layers. Each layer was a different shot. Although I selected 'attempt to align images in stack' when importing them, my first attempt at combining them using the Darken blend mode resulted in the sunspots being elongated as the sun tracked from left to right. Funnily enough, the sun still looked round, but the sunspots looked awful. I tried fudging it by cloning some of them out of the image, but it really didn't look good.

So I then had to painstakingly align each image manually, which I did by creating several ruler guide lines on the spots, before cropping and doing some final colour and sharpening edits. This is the final image and I have to say I'm quite pleased with it.

Isn't it nice when a plan comes together?

PLEASE REMEMBER THAT YOU SHOULD NEVER LOOK AT THE SUN THROUGH ANY OPTICAL INSTRUMENTS INCLUDING CAMERAS, BINOCULARS AND TELESCOPES WITHOUT USING A PROPERLY CERTIFIED SOLAR FILTER.

SUNGLASSES AND WELDING GLASS DO NOT OFFER ADEQUATE PROTETCION.